The Fall of the Wild by Ben A. Minteer

Author:Ben A. Minteer

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Columbia University Press

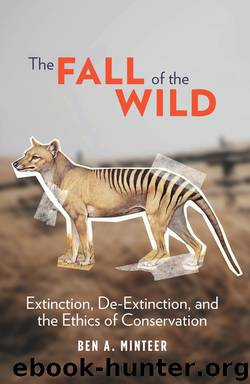

FIGURE 5.2 “Mr. Weaver bags a tiger.” This photo, which is believed to have been taken by the photographer Victor Albert Prout in 1869, is one of the very few nineteenth-century images of a thylacine known to exist.

Source: Public domain.

Despite its reputation as a bloodthirsty sheep killer, the empirical evidence doesn’t seem to support the view that the thylacine was a significant predator of sheep on the island. Some historians have even suggested that the bounty systems and the exaggerated claims about thylacine predation were attempts to veil the failures of an untenable and inexpert sheep industry, a situation that had far more to do with human incompetence and voraciousness than it did with the actions of marauding marsupials.6 Regardless, bounties and development drove the species into increasingly remote and hard-to-access territories by the late nineteenth century. By then, thylacine sightings, which had never been that common to begin with, were quite rare.

For decades, naturalists had been suggesting that the animal could be at risk of extinction if these trends continued. The British ornithologist and naturalist John Gould, a taxidermist for the Zoological Society of London (among other claims to fame, he acquired and named Darwin’s legendary Galapagos finches)7, went to Australia in the 1830s to document birds but also wrote about the state of the land’s mammals, including the thylacine. Although he believed that the dense forests of Tasmania would spare the animal from its fate for some time, it was a stay of execution rather than a permanent safe harbor for the species. As he wrote in The Mammals of Australia (1863): “When the comparatively small island of Tasmania becomes more densely populated … the numbers of this singular animal will speedily diminish, extermination will have its full sway, and it will then, like the Wolf in England and Scotland, be recorded as an animal of the past.”8

The thylacine would become a popular attraction in zoos, beginning in the 1850s at the London Zoo at Regent’s Park and soon in Europe and the United States, as well (figure 5.3). But although there were scattered calls for the conservation of Tasmanian wildlife and habitat at the turn of the century, there were very few efforts to breed the species in captivity and not much in the way of measurable progress in getting people to care about its plight.9 When William T. Hornaday’s Our Vanishing Wild Life appeared in 1913, the American conservationist had all but concluded that this “most interesting carnivorous marsupial of Australia” was doomed and that its “untimely end” would be cause for great regret.10

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4787)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4445)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4295)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3940)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3810)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3677)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3606)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3448)

Hedgerow by John Wright(3340)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3315)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3298)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3287)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3207)

Origin Story by David Christian(3185)

Water by Ian Miller(3166)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(3057)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2915)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2848)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2824)